I grew up in Nashville listening to the Grand Ole Opry on crackly car radios and later on, we were able to even watch it on our old black and white, three-channel, Motorola cabinet television. My father loved the Opry; he had grown up as a farmboy on the Tennessee-Kentucky border in a house with no electricity, and on Saturday nights, his family and neighbors would gather ’round the farmhouse’s living room radio—hooked up to their old truck’s battery—to hear Roy Acuff, Minnie Pearl, and Dad’s favorite group, the Carter Family. He even learned to play some Carter Family songs on an old hand-me-down guitar that borrowed strings plucked from the farmhouse’s front porch screen door.

Dad met Mom after they both returned from the war—he, as a tail gunner in the Pacific, and she, as a “Rosie the Riveter” in Detroit. After they were married, he found a job as a printing plate electrotyper in downtown Nashville, a block away from the Grand Ole Opry’s Ryman Auditorium, country music’s own Mecca.

Mom loved to sing, and though she did like my dad’s country music, I really think she preferred more of the big band type of music, especially Frank Sinatra and Dinah Shore. When my sister and I came along, my parents found a house in a modest Nashville suburb and set out to live the post-war American dream. At any rate, we always considered it a treat when Dinah Shore popped up on the old Motorola. Our parents would remind us that, having attended Hume-Fogg High School in downtown Nashville and then Vanderbilt University, Dinah was “a little ol’ Tennessee gal who did real good.” Mom would smile when Dinah sang her hit from the ’40s, “Shoo Fly Pie and Apple Pan Dowdy.” Dad would listen politely, but we all knew his heart was with the Opry. As for my sister and me, we weren’t so sure that any kind of pie made with flies sounded very tasty, whether they were wearing shoes or not.

I had the good fortune to meet Dinah Shore at a Doubleday Literary Guild party in Midtown Manhattan in the early ’80s. I was the Literary Guild Magazine’s art director at the time, and I had worked with her publisher in the marketing of one of her cookbooks. I spotted her as soon as I entered the ballroom, and I brushed past several other Literary Guild writers to talk to her. I told her I was a fellow Tennessean and she said, “We might be kin!” in a familiar accent, albeit so far from home. I also told her how we had grown up listening to her, especially, “Shoo Fly Pie.”

“Shoo Fly Pie!” she repeated, laughing as if she really was kin. “Did any of that Nashville guitar pickin’ wear off on you?” she asked.

“’Fraid so,” I told her, “The first song my dad taught me was the Carter Family’s ‘Wildwood Flower.’”

“The ‘Nashville Anthem’,” she said, wistfully.

“Yes ma’am,” I replied.

That evening I also talked to other Literary Guild writers, including Andrew Greeley about his “Cardinal Sins” and Peter Maas about “Serpico” and “Marie: A True Story,” his book about the downfall of a Tennessee governor, but it was the Dinah dialog that has hung in my memory all these years like a bright Christmas candle. And I was totally truthful about learning “Wildwood Flower.” My dad had played it all my life (and probably, most of his), and the fact that I learned it and mastered it sort of made up for all of the mechanical skills that I didn’t inherit or learn from him. I do know that it pleased him greatly when I added the guitar harmony alongside him as he played it.

As for the Grand Ole Opry, I knew that if I ever got to sing and play on its stage, it would have been a high point of both of our lives. We both knew it was a lofty aspiration, and my dad never would have pushed it on me as a career goal. However, in the back of my mind, I always dreamed that somehow I could slip in a side door at Opry.

And though Dad wasn’t around to see it, that side door was opened for me a few years ago. Dad had passed away in ’97, and though I didn’t think I could actually speak, much less sing, I was able to play “Wildwood Flower” on his old guitar at his funeral in the little country church where he and my stepmother were members. Dad’s pallbearers were his friends and church leaders from that same church, including Charlie Haywood, Charlie Daniels’ bass player since 1975.

The next time I would see Charlie would be backstage at the Opry, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

My journey to the side door of the Opry began with a phone call from Jerry Barr, a former co-worker of mine. He was handling the online sales for Carriage House; their signature products are King Syrup and Chicken ’n’ Ribs barbecue sauce. “Have you ever heard of Gaylord Entertainment?” he asked.

Nashville boy that I was, of course I knew. “They own the Grand Ole Opry and what used to be Opryland,” I told him.

“Carriage House wants to run a jingle on the Opry. Can you do that for us?” Jerry asked.

“What kind of a jingle?” I asked, “Something about syrup?”

“Yeah,” Jerry said, “Syrup. King Syrup is the main ingredient in something called ‘Shoo Fly Pie.’”

Somewhere up in Nashville, a side door creaked open. And, “Shoo Fly Pie,” the jingle, was written, recorded and shipped up to the Opry folks (http://www.bridgital.com/ShooFlyPie.mp3). That first Saturday night, I streamed the Opry on my Mac, and I could hardly believe my ears when I heard myself singing between the sets of some of the Opry stars.

“Shoo Fly Pie!” said Jim Ed Brown, the segment host after the jingle ran, “Y’all remember that?” Then he hummed a few bars from Dinah’s version.

When I spoke to the young Opry apprentice the following Monday, I worked up the courage to ask her if I could perform the jingle live on the Opry stage.

“Oh, I’m so sorry,” she said, “We don’t do that anymore…if we let you do it, we’d have to let everyone play their ads and jingles, and there would be way too much commotion up on the stage. However, we could get you in and let you sit at the back of the stage while it’s playing.”

“That would work,” I said.

“In fact, this week’s Opry would be a great one…Charlie Daniels will be here.”

And so, that’s how my sister, Jann, her husband, Lance, and I got to sit at the back of the stage while my voice, guitar and piano wafted over the airwaves and into the audience. I silently mouthed the words as the jingle played.

“What are you doing?” Jann asked.

“I’m Hillbilly Vanilli,” I told her. It was as close as I could get to performing on the Opry stage.

Then, Charlie Daniels took the stage, and his incredible a cappella rendition of “How Great Thou Art” stunned the crowd—and then brought them to their feet. After his set, Jann, Lance and I got to spend a few minutes backstage talking to Charlie Hayward, mostly about Dad. A few minutes later, Charlie Daniels joined us.

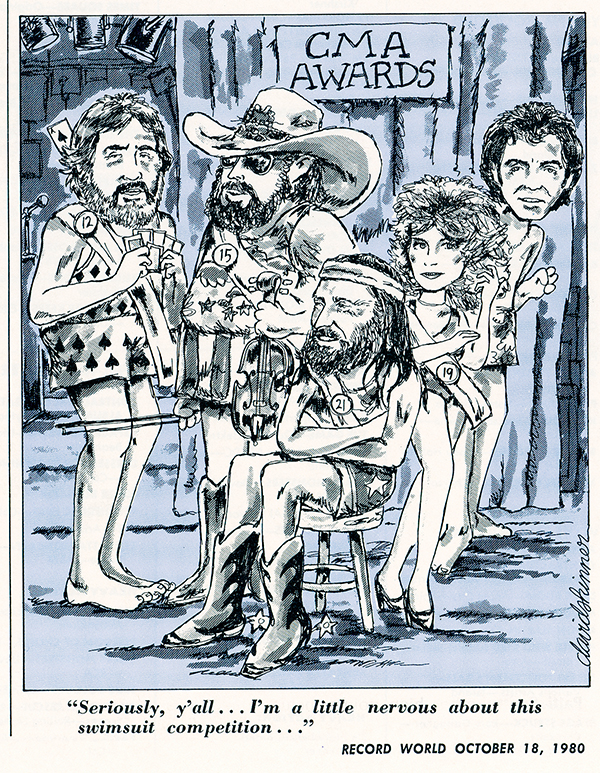

I had brought a couple of print-outs of cartoons I had drawn back in the early ’80s for Record World magazine, both of which featured Charlie Daniels. One of them, which I had drawn to highlight the 1980 CMA Awards, showed the finalists for that year’s Entertainer of the Year, and they were all dressed in swimwear. In the cartoon Charlie was saying, “Seriously, y’all…I’m a little nervous about this swimsuit competition…”

“I woulda been nervous about that!” Charlie remarked after I gave him the print-outs.

The following Monday morning, the young apprentice followed up with me.

“How did you enjoy the Opry?” she asked.

“It was incredible,” I said, “It kinda made me feel like Moses.”

“Why Moses?” she asked.

“Moses got to see the Promised Land,” I told her, “But he didn’t get to set foot in it.”

“Oh. That’s beautiful,” she said.

“Also, Moses played banjo,” I added.

“I did not know that,” she said.

“Yeah, he had a bluegrass band called ‘The Burning Bush Boys.’”

“Oh, I see,” she said, finally catching on. She did not sound amused.

And though Jann and I would go on to record yet another jingle (with the same tune) for Carriage House called “Chicken ‘n’ Ribs” (http://www.bridgital.com/ChickenNRibs.mp3), that golden night at the Opry would be our last visit there.

It was still a thrill to hear the new jingle twang through my Mac’s speakers for the next few Saturday nights, but it definitely wasn’t the same as being on the stage of the “Mother Church of Country Music,” or, since it was the new Opryhouse, maybe I should say, the “Daughter Church of Country Music.” As I listened from the warm confines of my suburban Atlanta home, in my mind I could almost see one Opry stagehand saying to another, “Hey, shut that side door over there…you’re letting flies in!”